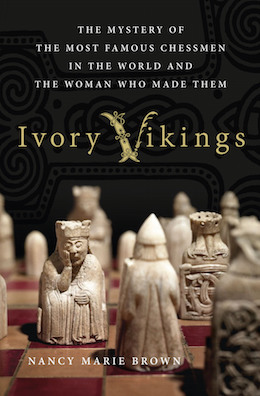

In the early 1800’s, on a Hebridean beach in Scotland, the sea exposed an ancient treasure cache: 93 chessmen carved from walrus ivory. Norse netsuke, each face individual, each full of quirks, the Lewis Chessmen are probably the most famous chess pieces in the world. Harry played Wizard’s Chess with them in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Housed at the British Museum, they are among its most visited and beloved objects.

Questions abounded: Who carved them? Where? Nancy Marie Brown’s Ivory Vikings explores these mysteries by connecting medieval Icelandic sagas with modern archaeology, art history, forensics, and the history of board games. In the process, Ivory Vikings presents a vivid history of the 400 years when the Vikings ruled the North Atlantic, and the sea-road connected countries and islands we think of as far apart and culturally distinct: Norway and Scotland, Ireland and Iceland, and Greenland and North America.

The story of the Lewis chessmen explains the economic lure behind the Viking voyages to the west in the 800s and 900s. And finally, it brings from the shadows an extraordinarily talented woman artist of the twelfth century: Margret the Adroit of Iceland.

Nancy Marie Brown’s Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them is available September 1 from St. Martin’s Press.

AS FAR AS THE POLAR STAR

Walrus ivory lured the Vikings to Greenland as well, we now believe, though the Book of Settlements tells a different tale. There, Eirik the Red, outlawed from Iceland for killing his neighbors, bravely sailed west and chanced upon Greenland. When his three years’ exile was up, this famous Viking explorer returned home and convinced twenty-four shiploads of Icelanders to colonize the new land with him in 985. Fourteen ships made it, carrying perhaps four hundred people.

The Book of Settlements hints that Eirik duped them, promising a “green land” more fertile than Iceland—which Greenland is not. Seventy- five percent of the huge island is ice-covered. Like Iceland, Greenland has no tall trees, and so no way to build seagoing ships. Farming is marginal. Only two places, Eirik’s Eastern Settlement of five hundred farms at the island’s southern tip and his Western Settlement, a hundred farms near the modern-day capital of Nuuk on the west coast, are reliably green enough to raise sheep and cows. But a good marketing ploy doesn’t explain why the colony lasted into the 1400s. Walrus ivory does.

A thirteenth-century treatise from Norway, The King’s Mirror, written as a dialogue between a father and son, concurs. “I am also curious to know why men should be so eager to fare thither,” the son says of Greenland. There are three reasons, answers his father: “One motive is fame and rivalry, for it is in the nature of man to seek places where great dangers may be met, and thus to win fame. A second motive is curiosity, for it is also in man’s nature to wish to see and experience the things that he has heard about, and thus to learn whether the facts are as told or not. The third is desire for gain.” Men go to Greenland, he said, for walrushide rope “and also the teeth of the walrus.”

By the time Greenland was discovered, Iceland’s walruses were a fond memory. They were never as numerous as the Greenlandic herds. Even now, walruses thrive along Greenland’s icy northwest coast, near Disko Bay, where Eirik the Red had his Northern Camp. It was not a nice place to work. In the Edda, written around 1220, Snorri Sturluson preserved a few lines of an earlier poem describing it:

The gales, ugly sons

of the Ancient Screamer,

began to send the snow.

The waves, storm-loving

daughters of the sea,

nursed by the mountains’ frost,

wove and ripped again the foam.

And that was the summer weather. The Northern Camp was a three-week sail north from Eirik the Red’s estate in the Eastern Settlement. From the Western Settlement it was closer—about four hundred miles, only a fifteen-day sail in the six-oared boats the sagas mention. Once there, cruising the edges of the ice sheet looking for walruses, the Vikings could see the easternmost rim of North America. One saga of the discovery of the Vikings’ Vinland traces this route: north to the walrus grounds, west across the Davis Strait, then south along the coast of Labrador to Newfoundland, where Viking ruins have been found at L’Anse aux Meadows. From there the Vikings may have explored all of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence south to the mouth of the Miramichi River and up the Saint Lawrence River toward present-day Quebec.

They found salmon and tall trees, wine grapes and self-sown wheat in Vinland, the sagas say, along with an overwhelmingly large population of hostile natives. Strangely, no saga mentions the vast herds of walrus on the Magdalen Islands off Newfoundland’s southwestern tip. It was here, in 1775, that hunters used dogs to cut through a herd of seven to eight thousand walruses, killing fifteen hundred beasts in one night. Hundreds of years before, the Micmac tribes summered in these islands, supporting themselves on walrus. A few bones that may be walrus were found at L’Anse aux Meadows, but if walrus ivory led the Vikings to Vinland, it wasn’t sufficient to convince them to stay. The encampment at L’Anse aux Meadows was lived in for only a few years, and no Viking settlements farther south have been found.

Vinland was very far to go. About two thousand miles from Greenland, it could be reached in nine days from Eirik the Red’s Northern Camp—if you were lucky. The crew of one replica Viking ship was at sea for eighty-seven days. You needed luck, as well, to return home with your cargo of tusks and hides. Even the most successful Vinland voyage in the sagas—the expedition in about 1005 by Gudrid the Far-Traveler and her husband, Thorfinn Karlsefni—lost two of its three ships. According to the Saga of Eirik the Red, Gudrid and Karlsefni were accompanied by two ships of Icelanders and one of Greenlanders, totaling 160 men. The tiny Greenland colony could not afford to lose a shipload of men. The six hundred known farms were not all active at the same time. At its peak in the year 1200, Greenland’s population was only two thousand. By comparison, Iceland’s population in the year 1200 was at least forty thousand.

Greenland’s labor shortage was severe. The time-consuming trips to the Northern Camp had to be planned around the summer chores required to survive: hunting the migrating seals, gathering birds’ eggs and down, fishing, berrying, and most important, haymaking. The walrus hunt began in mid-June (after the seals left) and ended in August (before the haying). Four or five boats would row north, each crewed by six or eight men—the most that could be spared from the Western Settlement’s hundred farms. It was a dangerous undertaking. Men died not only from shipwrecks and exposure but during the hunt itself: As we have seen, walruses are not easy prey. It was also profitable. According to one calculation, each of the Greenlanders’ six-oared boats could carry an estimated three thousand pounds of cargo: That’s about two whole walruses, or twenty-three walrus hides and heads, or 160 heads alone.

To save on weight, the hunters chopped the skulls in two and took only the tusked upper jaws south. There the tusks were worked free of the jaws over the long winters. It took skill and training—but every farm in the Western Settlement, it seems, had someone assigned to the task. Chips of walrus skull have been found on large farms, on little farms, even on farms a long walk from the sea. The chieftain’s farm of Sandnes—where Gudrid the Far-Traveler once lived—may have been the center of the industry. Walrus ivory was extracted there for 350 years, longer than at any other farm, and the amount steadily increased from the year 1000 to 1350. The Sandnes ivory workers also grew more skilled at their trade, leaving fewer chips of ivory as compared to chips of jawbone.

From the Western Settlement, the ivory was shipped south to the Eastern Settlement. It seems to have been stored in the large stone warehouses at the bishop’s seat at Gardar, which—with barns for a hundred cows and a grand feast hall—was the biggest farm in Greenland. A haunting find in the churchyard there hints at the walruses’ cultural importance: Archaeologists unearthed nearly thirty walrus skulls, minus their tusks, some in a row along the church’s east gable, others buried in the chancel itself.

Greenlandic ivory found a ready market. Modern museum inventories of ivory artwork show a spike around the year 1000, soon after Greenland was settled. The popularity of walrus ivory continued to rise through the next two hundred years, and Greenlanders strove to meet the demand: The waste middens beside their farms become richer and richer in walrus debris. In the 1260s, when the Greenlanders, like the Icelanders, agreed to accept the king of Norway as their sovereign, King Hakon the Old made it clear that his jurisdiction extended all the way north to the walrus hunting grounds. His official court biographer, the Icelander Sturla Thordarson, wrote in a verse that the king would “increase his power in remote, cold areas, as far as the Polar star.”

How much ivory came from Greenland is hard to know. The only historical record tells of the shipment sent by the bishop of Greenland to Bergen in 1327 in support of a crusade. Estimated at 520 tusks, or less than two boatloads from one year’s hunt, that one shipment was worth 260 marks of silver, equivalent to 780 cows, sixty tons of dried fish, or 45,000 yards of homespun wool cloth—more than the annual tax due from Iceland’s four thousand farms that year.

Another indication of the riches available in Greenland comes from the fourteenth-century Saga of Ref the Sly. Set in the days of the settlement, it’s a picaresque tale of a master craftsman whose foul temper and violent overreactions get him kicked out of Iceland, Norway, and Greenland. He and his family are finally taken in by the king of Denmark, who is pleased to learn that “they had a wealth of ropes and ivory goods and furs and many Greenlandic wares seldom seen in Denmark. They had five white bears and fifty falcons, fifteen of them white ones.” Earlier in the saga, the king of Norway ordered one of his men to sail to Greenland and “bring us teeth and ropes.” It was to win the Norwegian king’s aid against Ref the Sly that the Greenlanders sent, as well, a gold-inlaid walrus skull and a walrus ivory gaming set made for playing both the Viking game of hnefatafl and chess or, as one translator construes it, “both the old game with one king and the new game with two.”

The Greenlanders kept very little ivory for themselves. They carved the peglike back teeth into buttons, they made tiny walrus and polar bear amulets and a miniature figurine of a man in a cap, and they fashioned a few ivory belt buckles, like the one found with the Lewis chessmen. But only two pieces of more elaborate ivory artwork have been discovered in Greenland.

One is a broken chess queen, picked up by a Greenlandic hunter from the remains of an Inuit summer camp on a small island close to the modern town of Sisimiut, about halfway between the Vikings’ Western Settlement and their Northern Camp. The hunter presented it to the queen of Denmark in 1952, and though it passed from Queen Ingrid’s private collection into that of the Danish National Museum in the 1960s, it was not put on display until the early 2000s. No one has mentioned it before in connection with the Lewis chessmen, though the visual similarities are striking: The Greenland queen is roughly the same size. She is seated on a throne, though hers has a higher back or hasn’t been finished— the ivory is in such poor condition, it’s hard to tell. The Greenland queen wears a rich gown, though the folds in her dress are sharper and more V-shaped than the pleats on the Lewis queens’ gowns. She rests her left hand on her knee; her right arm is broken off and her face and chest are chipped away, so we cannot say if her right hand touched her cheek.

The second work of art found in Greenland is the ivory crook of a bishop’s crozier. Adorned with a simple chevron design, the center of its spiral is filled with four curling leaves in the graceful Romanesque style, which displaced Viking styles of art throughout the North in the twelfth century. The crozier was discovered in 1926 buried with a skeleton under the floor of the northern chapel of the large stone church at Gardar. The archaeologist who excavated the grave dated the crozier stylistically to about 1200. He suggested it was made for Bishop Jon Smyrill, who died in 1209, by Margret the Adroit, who is named in the Saga of Bishop Pall as “the most skilled carver in all Iceland.” And so we bring our next chess piece onto the board: the bishop.

Excerpted from Ivory Vikings: The Mystery of the Most Famous Chessmen in the World and the Woman Who Made Them © Nancy Marie Brown, 2015